It’s barely 10 a.m. on a July morning. The sun is blazing, there’s no wind in sight, and you're mowing a lawn, washing windows outdoors, or working on a construction site with no air conditioning.

Suddenly, your coworker stops, clearly dizzy. Their face is flushed, their breathing is shallow, and they say their head is spinning. Heat stroke? Very likely.

When working in hot environments, whether outdoors or indoors, you have to be vigilant. Because heat stroke doesn’t take a break.

Working in the heat is more complex than just “it’s hot out”

The temperature isn’t just what your phone shows. The feeling of heat can vary a lot depending on whether you're in a poorly ventilated room, a shaded outdoor area, or standing in direct sunlight at noon.

That’s why CNESST suggests evaluating the real conditions by factoring in :

-

actual air temperature

-

humidity level

-

air movement

-

solar radiation

In other words, it’s about measuring the actual heat the body experiences.

How to calculate corrected temperature

🧠 From this point on, grab your calculator or a pen and paper. Here’s how our teams evaluate corrected temperature, based on CNESST guidelines.

🔹 Step A – Take the air temperature in the shade

Use a thermometer or a weather app to find the temperature in the shade at your work location.

🔹 Step B – Adjust based on relative humidity

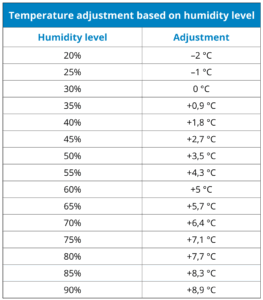

Use the following table to adjust the temperature according to the humidity level:

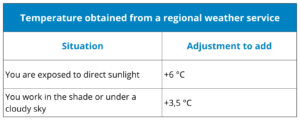

🔹 Step C – Adjust based on sun exposure

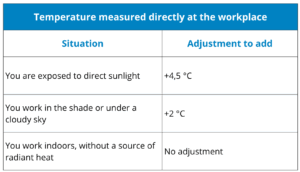

If you are measuring the temperature directly on site:

If you are using a local weather app:

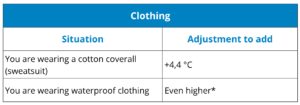

🔹 Step D – Adjust based on clothing

Clothing plays a major role in the body’s ability to release heat.

💡 The less breathable your clothing, the faster your body heats up. Be especially cautious with impermeable fabrics.

Physical effort also matters

Working in the sun is one thing. Working in the sun while constantly moving is something else entirely. The more effort you exert, the more heat your body produces. To cool down, it needs to sweat more. That leads to faster dehydration and higher heat stroke risk.

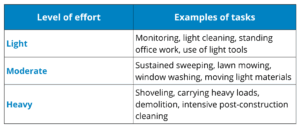

CNESST categorizes tasks into three intensity levels. Here are some concrete examples:

🧠 Remember: two people exposed to the same outdoor temperature won’t feel the same heat especially if one is sweeping a floor and the other is hauling 20 kg bags up a staircase.

In fact, even moderate heat can become dangerous when physical effort is high, especially if combined with heavy clothing and poor hydration.

Clear recommendations

By now, you have:

- Recorded the ambient temperature

- Applied the adjustments based on environment and clothing

- Identified the level of physical effort involved

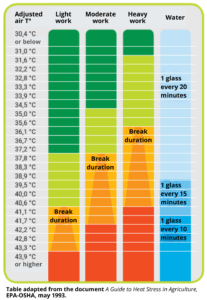

Now, use the final number to refer to the table below and determine:

-

how much water to drink

-

how long your breaks should be

If your result falls between two values, use the higher one.

Quick guide to the color-coded zones:

🟩 Light green zone: Low risk. Temporary measures should be discussed with your employer to ensure working conditions remain safe.

🟨 Yellow zone: Rising risk. Preventive measures must be implemented. Increased vigilance is recommended.

🟥 Red zone: Very high risk. Enhanced prevention is mandatory to maintain safe conditions. Maximum vigilance required.

🟦 Blue zone: Relates to hydration recommendations.

👉 1 glass = 250 ml (8 oz)

👉 Never drink more than 1.5 litres of water per hour, even in extreme heat.

💡 These guidelines are designed to prevent heat-related illnesses before they become serious. Even if you feel fine, following the rules is crucial.

In summary

Working in the heat isn’t about personal tolerance. It’s about prevention. No matter the task or environment, there are simple and effective ways to reduce risk:

✅ Drink water regularly

✅ Adapt your work pace

✅ Take frequent breaks

✅ Wear breathable clothing

✅ Listen to your body and your coworkers

Because in the end, no job is worth risking your health.

📌 All data, charts, and recommendations presented in this article are taken from the official CNESST website: Travailler à la chaleur : mesures préventives.